As architects, we spend a lot of time thinking about scale — from city-wide infrastructure down to the craft of a handrail. But some of the most impactful work we do isn’t about the scale of objects — it’s about the scale of relationships.

The “One-Fifty Rule” is a concept drawn from evolutionary anthropology, psychology, and organisational theory. It builds on the work of Robin Dunbar, who famously proposed that human beings have a cognitive limit to the number of stable social relationships we can comfortably maintain — around 150.

It’s a small enough number that people recognise each other, feel part of a shared identity, and understand the social norms of the group. It’s also just big enough to sustain diversity, resilience, and a sense of scale. In the context of design, that number offers something surprisingly rare: a human-centred metric we can actually build with.

Why 150 Matters

The 150 rule isn’t a magic number, but it’s a powerful guideline. It’s been observed in indigenous communities, military units, intentional communities, sports clubs, schools, even the optimal size of teams within successful global companies. When group size pushes much beyond 150, a shift occurs: people stop recognising each other, informal systems give way to bureaucracy, and shared purpose can begin to fray.

From a design and planning perspective, this threshold gives us a natural unit for organising large systems into coherent parts — pods, cohorts, neighbourhoods, teams — where cohesion and accountability are strong. Whether we’re talking about schools, workplaces, stadia, or residential communities, embedding the 150 rule can make the difference between anonymous sprawl and vibrant civic life.

From a humane point of view, from a village from India to the Cotswolds, the 150 principle is a place of nostalgic yearning. The sense of traditional Indian village community as portrayed in Balkrishna Doshi’s Writings on Architecture and Identity has global resonance as we seek to find a sense of order in an increasingly digitised world. This sense of identity has its roots in understanding how social groups, the 150, work.

The Brain and the Built Environment

Robin Dunbar’s research — and the broader field of social brain theory — suggests that our brains evolved not just for survival or tool use, but to manage complex social relationships. Human social groups have natural “layering” — five intimate friends, fifteen trusted allies, fifty good friends, 150 meaningful relationships. These rings are not arbitrary — they reflect our emotional and cognitive bandwidth.

What’s remarkable is that these layers map neatly onto spatial and organisational strategies. The inner circle of five might be your project team. Your fifty could be a community of practice or a cohort in a workplace. And your 150 is the full team, the club, the year level, the pod.

So what happens when the built environment honours these limits? You get environments where people know each other, look out for one another, and feel a sense of belonging. You reduce the friction that comes from scale and anonymity. You design for social sustainability, not just material or environmental sustainability.

From Theory to Practice

What does this look like in real-world terms? It might be:

- A school designed with learning communities of no more than 150 students per year or house.

- A stadium with active supporter bays of 150 people, each with their own zones, access, facilities, and rituals.

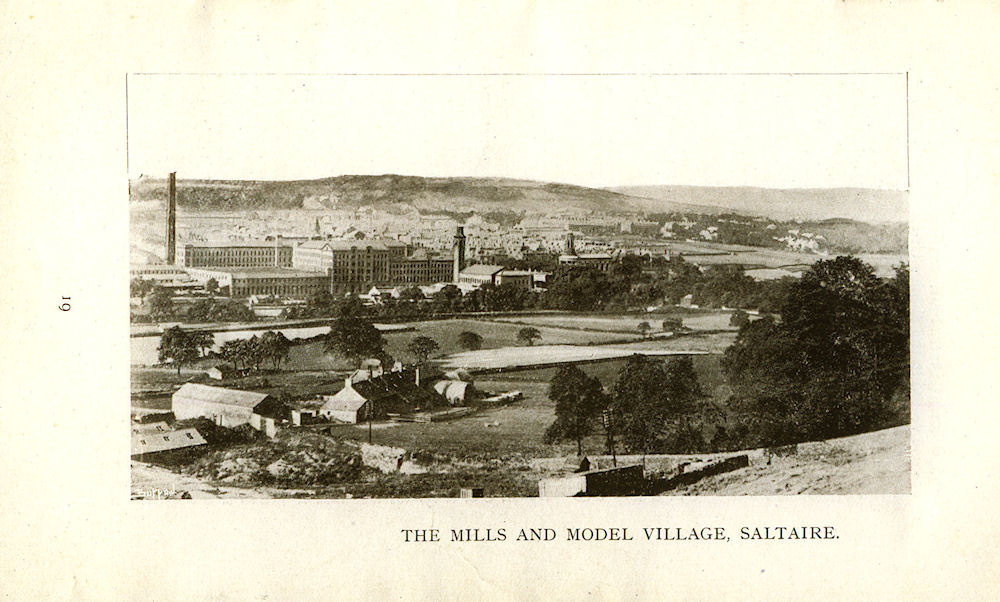

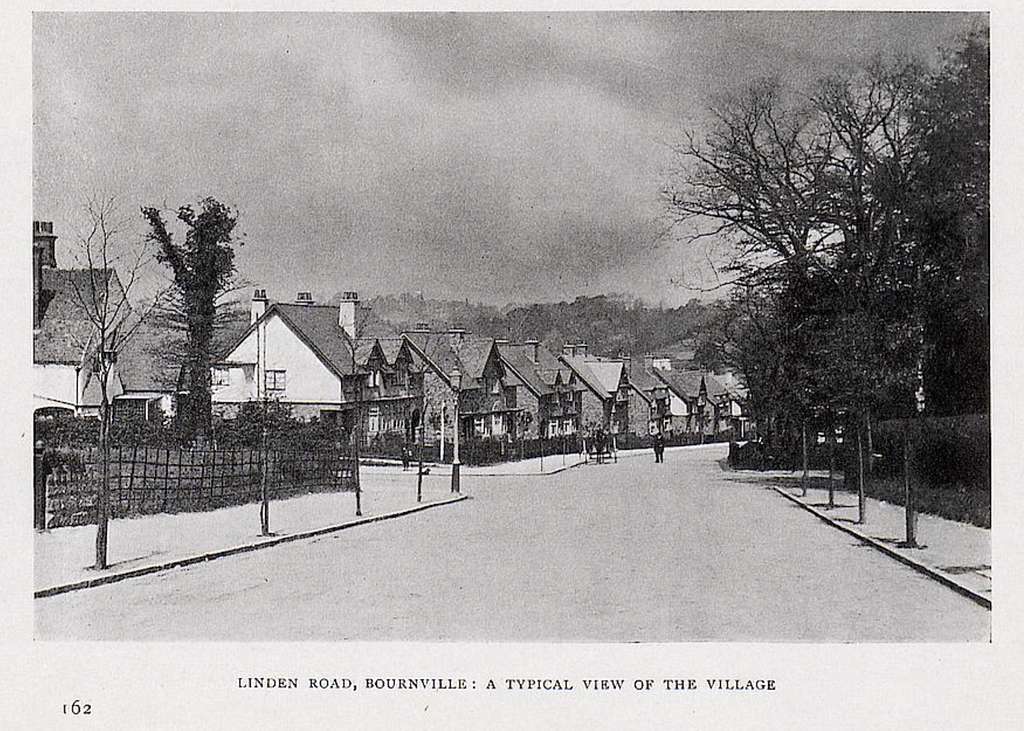

- A housing development broken into pocket neighbourhoods of around 30–40 dwellings — enough to form three or four strong 150-person social clusters. The work that Nightingale have undertaken in the development of the exponential network or in the social ideals of the Interlace in Singapore that breaks down the typical high rise apartment building into an interlinking series of neighbourhoods all extoll these values. Historical examples, such as Saltaire and Bourneville, developed by Victorian Industrialists, similarly fostered community through cohesive neighborhoods.

- A workplace that splits into self-managing units grouped at 150, each with their own identity and rhythm, even within a much larger company.

This isn’t about shrinking everything. It’s about nesting scales: using 150-person pods as building blocks for larger systems, each with its own identity, leadership, and connections. A stadium of 30,000 becomes a village of interconnected tribes.

Why It Works

The 150 principle works because it aligns natural human behaviour with physical form. It creates clarity, continuity, and care. From a client’s perspective, the benefits are clear:

- Stronger community outcomes: People feel connected, valued, and engaged.

- Improved operations: Teams function more efficiently when relationships are known and stable.

- Safer environments: In emergencies or high-pressure settings, familiarity supports calm and coordination.

- Economic value: Spaces that work for people are better used, more loved, and perform better over time.

There’s a compelling infrastructure logic here, too. Designing to human scale means you can optimise access, reduce waste, and target investment. In stadia, it means knowing how to cater to supporter groups without overbuilding. In schools, it means targeting your staff ratios and social support systems for maximum effect.

Designing for Social Cohesion

At the heart of this is a simple truth: scale is not neutral. The built environment either supports or undermines our capacity to connect with each other. We’ve all experienced places that feel alienating — too big, too loud, too anonymous — as well as those that feel instantly welcoming. The difference is often how the space has been scaled to human needs.

As architects and planners, our job is to make places not just functional, but socially legible. The 150 rule is one of the best tools I know for achieving that. It’s evidence-based, adaptable, and — once you see it — impossible to unsee.

In the essays that follow, I’ll explore how this principle can reshape how we think about sporting and public assembly buildings, residential neighbourhoods, and workplace environments. Because whether we’re building a stadium or a studio, a campus or a community, the key question remains the same: does this space help people thrive together?

Leave a comment