What if the key to liveable cities is not only how many homes we build, but how many neighbours each of us can meaningfully know?

As Australia, the UK, and cities globally grapple with housing affordability, densification, and urban renewal, an overlooked truth remains constant: humans are wired to thrive in communities of around 150 people.

If we overlook the human scale, we risk building loneliness into the bones of our cities. But if we design neighbourhoods at the scale where trust can form and belonging can take hold, we unlock a more liveable, responsible, and hopeful urban future.

Anthropologists describe this threshold – Dunbar’s Number – as the cognitive limit at which we can maintain genuine social relationships. It is the scale where trust takes root, where reciprocity emerges, and where we can know and be known. Beyond this, anonymity grows, responsibility diffuses, and the social fabric thins.

At around 150 people, we still greet others by name, notice if someone needs a hand, and participate in the small acts that turn density into neighbourhood. We borrow a ladder, share a herb garden, check in on an elderly resident, ask a neighbour to collect the kids if we’re caught at work. These behaviours are not sentimental – they are the foundations of safe, resilient, and socially sustainable cities.

And importantly, the 150 rule does not oppose density – it structures it.

A Pattern Across Time and Culture

This number is not a theory invented for planners; it is a constant visible across history.

In Australia, mid-century walk-ups and the classic “six-pack” apartment typology naturally clustered around this scale. They delivered density lightly – medium-rise, shared stairs, open landings, communal gardens – and they quietly built durable communities.

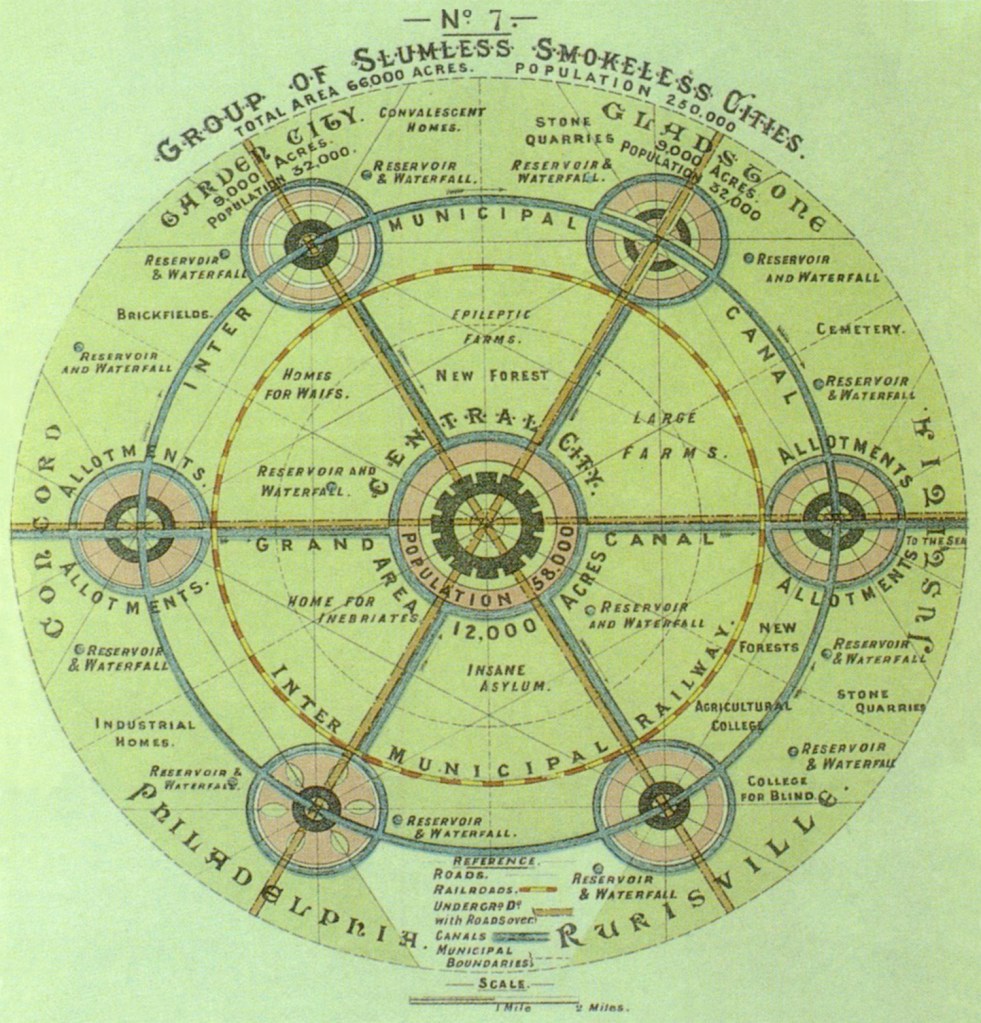

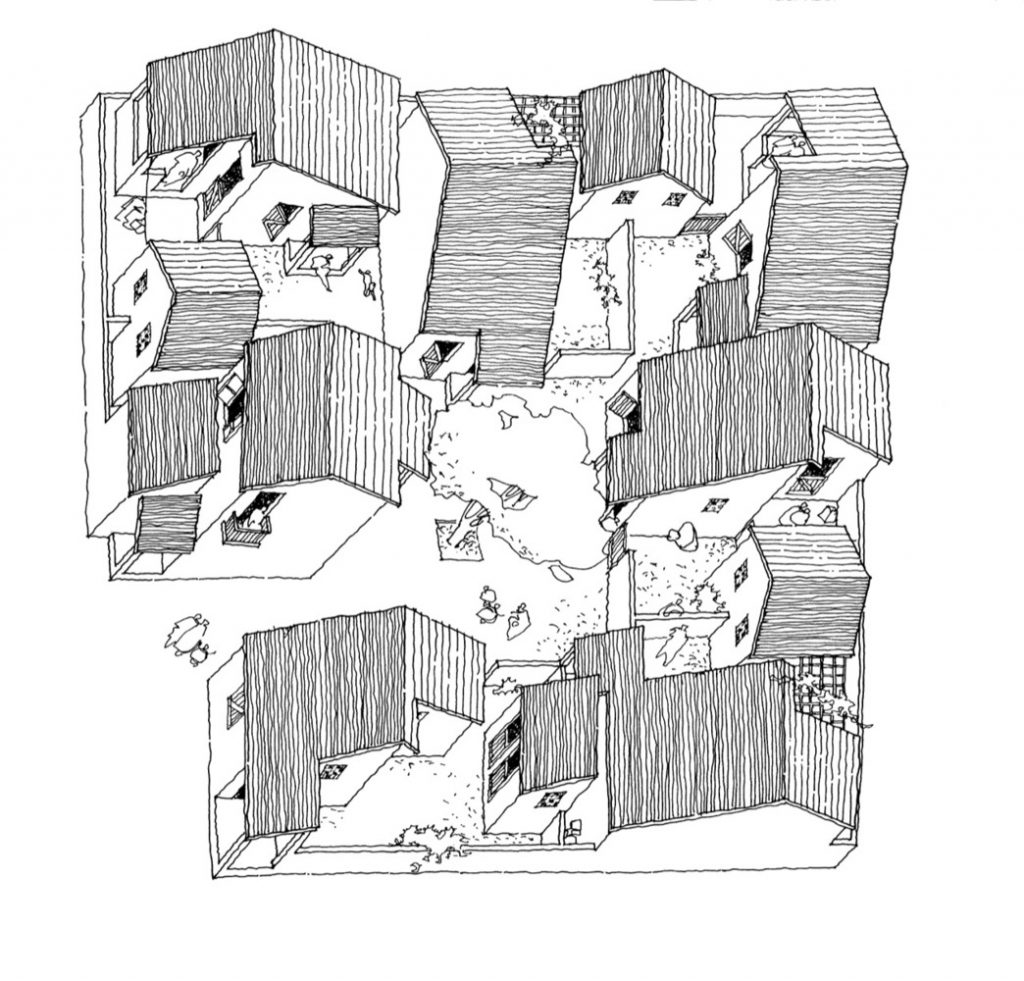

Internationally, the pattern is just as clear. Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City neighbourhood units, with around 150–200 households, sought to balance privacy with shared life. Vienna’s municipal housing often organises thousands of residents into recognisable social courts. Charles Correa’s Belapur Housing in India stacks intimacy into density: clusters of 6–8 homes aggregating upwards to ~150 people.

Even medieval hamlets, North African courtyard compounds, and Southeast Asian village clusters gravitated around this number – not because of planning policy, but because it is what humans naturally sustain.

Human-Scale Thinking in a High-Density Century

Modern urbanism has returned to this idea: true city life functions in recognisable social units.

Christopher Alexander, in A Pattern Language, articulated neighbourhood patterns that support familiarity and safety. Jane Jacobs framed urban vitality through “eyes on the street” – ordinary people recognising each other across daily routines. Jan Gehl’s people-first cities champion proximity, encounter, and the everyday theatre of shared space.

And in contemporary practice, cities like Copenhagen, Singapore, and Vienna show that density works best when broken down into coherent clusters – vertical villages, not anonymous megablocks.

For example, at the UN17 Village in Ørestad, Copenhagen, the development is explicitly framed as “a modern village” built around communal facilities, sharing and neighbour-linking — a Community Manager is appointed, and the design embeds social connection and resource-sharing at its core.

This real-world experiment demonstrates how even large mixed-use schemes can operationalise the 150-person cluster logic: not simply by reducing density, but by organising it into recognisable social units, with shared spaces, active encounter, and clear identity.

The logic is simple: a city of villages works better than a city of crowds.

Regeneration, Scale and Trust

In major redevelopment precincts the risk is not height or yield. It is psychological distance. We have global cautionary tales of super-tall residential districts where density was delivered without social structure. Equally, informal settlements and favelas — while materially constrained — often demonstrate strong micro-communities. The lesson is clear: if we are rebuilding, we must understand and support the social units that already existed, and ensure large buildings are structured to nurture community, not erode it.

This is where the 150 rule becomes a design tool. It invites us to ask:

- How do our designs acknowledge — and strengthen — the social and anthropological structures people naturally form?

- How do we break large projects into socially comprehensible neighbourhoods?

- Where are the thresholds of arrival, belonging, and shared identity?

- Which shared spaces cultivate repeated, informal contact – corridors, rooftops, gardens, mail rooms, gyms, co-working lounges, play terraces?

- Who holds community memory and helps weave it – a concierge, a building host, a resident committee?

At ~150 people, responsibility is personal, not abstract. People notice. People care. And cities become more than infrastructure; they become living networks of stewardship and reciprocity.

The Social and Economic Dividend

Neighbourhoods built at human scale deliver concrete benefits:

- Lower turnover and vacancy

- Higher resident wellbeing and safety

- Social support for ageing populations

- Reduced strain on services and health systems

- Stronger, hyper-local economies – the bakery that survives, the childcare co-op that forms, the weekend market that grows

- Greater environmental sustainability through shared resources and smaller ecological footprints

Isolation is expensive. Cohesion is efficient.

Designing for Belonging in the Future City

As build-to-rent expands, as infill intensifies, and as regeneration precincts reshape global cities, the opportunity is not to return to villages – but to embed village logic inside the metropolis. A major residential development can and should be understood and delivered as a cluster of villages — distinct, legible social units — to embed social sustainability at the core of density.

If we create environments where people genuinely want to live, put down roots, and build community, the value proposition strengthens for everyone. Developers benefit from safer, more stable and desirable places — homes where people stay, participate and look after their environment. When housing shifts from speculative asset to lived-in community — a place to grow, contribute and belong — the upside is shared socially and economically.

This might mean:

- Clustering ~150 residents behind shared entries and communal thresholds

- Consider giving clusters their own identity or purpose — a library or shared workspace in one, allied health in another, dining or recreation in a third. This encourages movement, interaction and familiarity across the wider precinct, strengthening social fabric while preserving the intimacy of the 150-person scale.

- Designing rooftops, gardens, courtyards, and maker spaces as social engines

- Digital neighbourhood platforms for coordination, care, and shared culture

- Viewing foyers, laundries, bicycle rooms, and mail zones as opportunities, not back-of-house residue

- Assigning stewardship roles that encourage participation and pride

- Design the “edges” where private life meets shared space so that interaction feels natural, not forced. Communal areas should invite connection rather than create thresholds of exclusion. A community in which you nod at a neighbour, because you bump into each other at the supermarket every Tuesday, is stronger than one in which people travel to shop, or to eat out, or to work out.

In short: designing for recognition instead of anonymity.

If we overlook the human scale, we risk building loneliness into the bones of our cities. But if we design neighbourhoods at the scale where trust can form and belonging can take hold, we unlock a more liveable, responsible, and hopeful urban future.

The 150 rule is not nostalgia. It is neuroscience. It is anthropology. And it is a blueprint for the next generation of urban housing – from mid-rise infill to major precinct regeneration.

To build cities fit for the next century, we must design places where we can know and be known.

Not to recreate the village – but to restore the village within the city.

Leave a comment